Bartlebee Brands Factory Number Nine

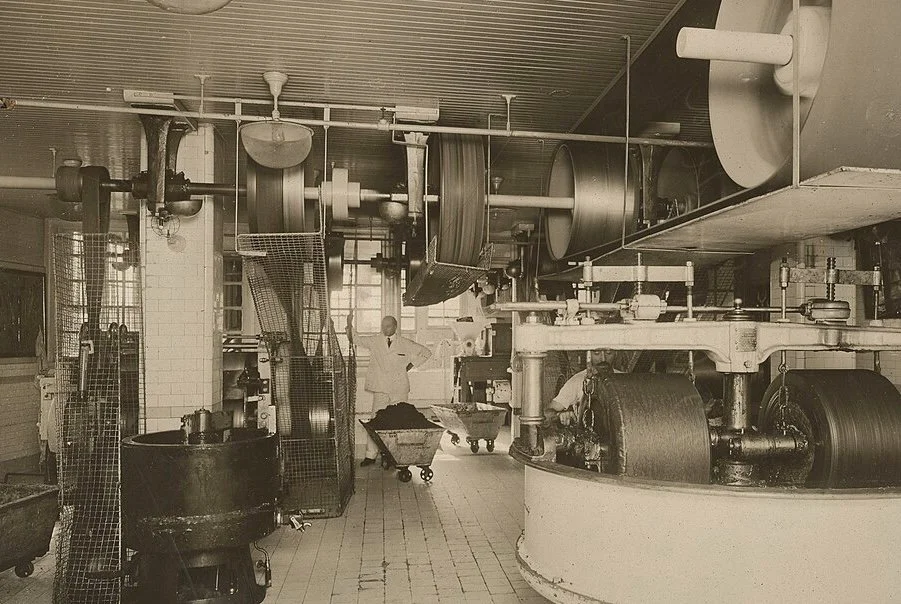

Two workers use large mixing machines inside the factory

To those who have been following the Creative Library for some time now you probably have noticed a bit of a difference with this update. Namely, that while previous updates have focused on a wide variety of subjects, people and companies, they have always tied into art in a very direct way. From the Dorothy Do fanclub to the Punk bands of old, the history articles have always had a thread, no matter how loose, back to the characters hosted in the archives. This update is really pushing that thread, as you will see the selection of creative history articles this update are centered around Bartlebee Brands as a company. We tackle the history of unionization efforts, Factory Number Nine, and of course the creator of Beetrice. I feel that I will get questions about the relevance of such articles on this site. The factory was for making candy not art; how do the labor struggles of factory workers tie into creative history?

See, small as the connection to the arts might be, I feel it would be a disservice to discuss Beetrice without also looking at the activities of the company she represented, much in the same way as we will eventually discuss Telectrica and Tellie Lectric. It is important to see what Beetrice as a concept stood for and to get as many details and enriching pieces of history related to her as possible, because without them it just wouldn’t be as interesting to discuss the character. If not just because information about the behind the scenes of her various animations and movies are very difficult to come by. With just those aspects we would have a very barebones update on our hands. With that in mind I think there is no more exposition needed for us to get into our first article of the update: Factory Number Nine.

A man in a white suit watches over the machinery.

Factory Nine. Oh Factory Number Nine, one of the most brutal structures in labor history, responsible for the creation of numerous labor laws, case studies on worker rights, safety hazards, workplace racial violence, and countless other changes that have transformed the face of the American work environment. Yet for all these things, the factory is hardly known today, discussed only in the rare urban exploration threads or cited in the margins of biographies. Maybe that would be for the best, letting this place fade away, if not for just how important it is to remember the harm caused by this factory.

In a just world, Factory Number Nine would not have been built, as the mere opening of its doors signaled the start of years of accidents, riots, murders, injuries and more. Just by existing the factory spoke to the violence Bartlebee Brands was capable of.

First envisioned by CEO Aaron Fulch as the crown jewel of the company, this factory would change everything for Bartlebee Brands. For years the factory had existed only as the dream of Fulch, with the board of directors insisting that it would be too costly and too inefficient to create a factory of the proportions he had in mind. Yet Fulch refused to listen. He wanted to create something special, something wonderful: a structure that would last forever and serve as a monument to the company he had helmed for so long. Ultimately the company would buckle to their CEOs demands. Beginning in 1935, the construction of this factory was described as a hellish experience for the workers involved.

The land chosen for the factory to be built on was unstable, eroding, and constantly battered by terrible weather. For all his talk of this factory being the most important project the company would ever take on, Fulch was incredibly lax and cheap with the safety and quality of construction. Many workers died in accidents whilst building the structure and at one point a landslide demolished the half formed factory, forcing the company to start again. This time around, the board of directors took control of proceedings, bringing on board expert architects and engineers, and being extremely thorough with the construction of the factory while a slighted Fulch groused his disapproval from afar. From then on the area was populated with several native and non-native plants courtesy of Bartlebee Brands in an attempt to stabilize the ground. The plants took and so too did the popular image of the factory as a sunny green place.

Through intense hardship and the efforts of many workers, the factory was finally completed in 1941. It was a sullen day when the factory opened; with record downpours, the small crowd attending the opening ceremony was forced to take shelter under the entrance awning. Fulch was insistent that the first to enter the newly opened factory was to be one of its workers and thus those in attendance waited miserably under the factory's shadow until the weather alleviated. Upon research weather reports show that following the growth of Bartlebee's garden the area received less severe weather throughout the years, which I suppose is lucky on the owners part.

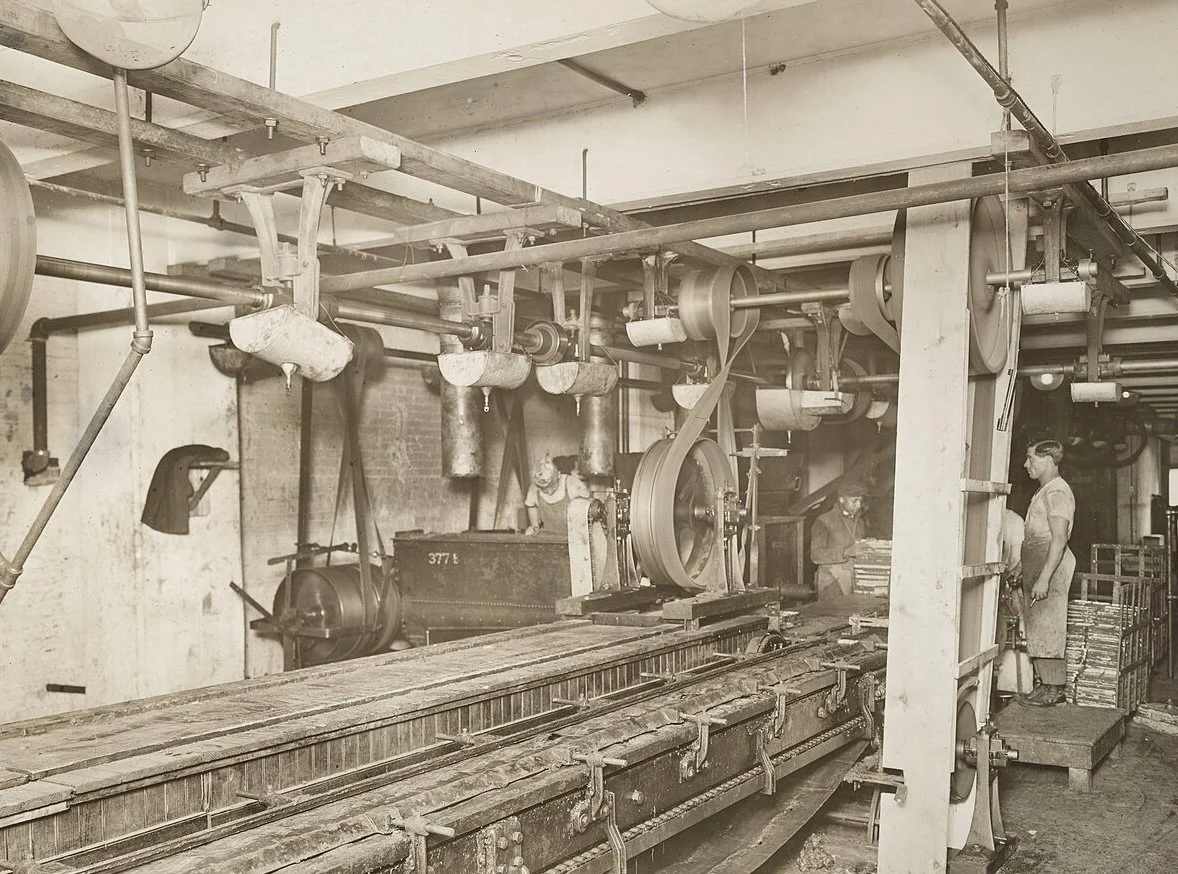

A conveyor belt inside the factory.

Upon opening the factory, Fulch remarked that it was “to one day be among the most important structures in American history.” Had he known what would become of his factory he’d likely have been very pleased with himself. Unfortunately for Fulch he would not survive to see the legacy built by this factory, as following his visit he would soon pass away from undisclosed health complications. It was a somber note to herald the factory's opening - maybe a sign of things to come. In regards to the factory itself, the building was an architectural marvel with several floors stacked so high they nearly blotted out the horizon. Not only this but the factory took the form of a honey comb, with the six sides of the building each being dedicated to different tasks. The factory garden, located at the center of the hexagonal structure, was equally marvelous. It grew just about every flower imaginable and drew in crowds of tourists from all over the country who visited just to get a look at the botanical wonder. The garden was heavily populated with Bartlebee Brand raised honey bees, as well as several other exotic pollinators which is to say that the garden must have been quite a sight to see in its prime.

Of course, as is always the case with Bartlebee Brands, the faults began to show soon enough. Although the building was impressive in both scale and architecture, it was perhaps too big for its own good. The hexagonal arrangement meant that traversing from one section of the factory to the other was a time consuming slog, especially since non-gardeners were not allowed to cut through the gardens. The bee colonies hosted within the garden would often create offshoot hives in whatever dark corners of the factory they could find, which often meant risk of contaminated product as well as increased operational costs related to hiring exterminators and building repairmen. It is with this in mind that one can assume the constant “hum” bemoaned by Factory Nine workers might have been a result of bees nestling in the walls and crawl spaces.

Several woman sit sorting candies from trays.

In the early days of its operation the factory also was not ventilated properly, with workers often experiencing dizziness and even passing out at their work station which led to further accidents. This is not hard data, but workers at Factory Number Nine on average experienced more accidents and injuries than those at other Bartlebee Brand factories and those helmed by other companies. Prior to its closure, stories ran abound of workers falling into mixing vats and never being seen again, or getting their hands stuck in machinery that proceeded to slowly pull them in. Death was a constant occurrence for the Factory Nine workers, as was the callous disregard for it by upper management. As discussed in our article on factory rules those in charge did little if nothing at all to mitigate the harm taking place on the factory floor. Instead, they had their sights set on things like the intense (but not uncommon) segregation of their work force; and in this area Factory Nine was notoriously brutal. Workers at the factory made the same standard rate as other factories, 40 cents per hour - but if you were a black man you only made 30 cents per hour, and in the cases of black women? 25 cents per hour. Needless to say this was unsustainable. If a white worker was injured or ill they often had their pay docked, while in the case of non-white workers they often ended up fired and immediately replaced.

On its interior, the factory was a hive of abuse and mistreatment, and on the exterior conditions did not fare much better. One such example being the hippie shootings of 1966, in which several students and local hippies performed a sit-in at the factory. This event, in which organizers blocked the entrance to the factory beginning in the early morning, was intended to protest the environmental damage being done by Factory Number Nine and Bartlebee Brands at large, as well as to decry the companies contributions to the American military. Bartlebee Brand's involvement with the United States military complex was always a minor aspect of its function with patriotic messages supporting the troops in their advertising, but this would change following the 1964 World's Fair incident. Bartlebee Brands began directly donating proceeds towards the war effort as well as sending food and candy to the soldiers. The intention of the protesters was to stop this support, or at least slow it down through preventing people from heading in to work at the factory. However on the fifth day this peaceful occupation would soon devolve into violence when irritated members of the staff began to beat and batter the protesters. Panic soon broke out amongst those gathered culminating in the national guard, (who were called in at the first day of the protest) opening fire on protesters and killing six: Harley Young, Isaac Owens, Elmira Long, Will Kirk, Betty Sawyer, and Lou Williams.

The aftermath of this event was complicated. The six dead protesters were smeared on national television by the president himself - friend of current Bartlebee CEO Ken Ruxfield - who called the sit in an “Internal attack on our liberties and freedom as Americans,” while the press of the time was extremely vague and generally obfuscated the details of why the protest happened in the first place. From then on the hippie movement would dwindle and die out, being labelled a threat to America’s ways of life and generally having their image reduced to that of a shallow caricature. Researching the years following this, one may find multiple articles concerning incidents in which hippie groups were killed or attacked by patriots. In regards to Bartlebee Brands, Factory Number Nine continued business as usual not even a day after the shootings. The Factory Nine Union also vehemently denied involvement in the initial attack on the protesters, but this does not hold up to scrutiny which is extremely disappointing.

The unionization efforts of the Factory Nine workers have been split into their own article as I feel it is only right, but needless to say Factory Nine remained an ugly stain on the labor landscape right up until 1978 when in an effort to save the now struggling company, leadership decided to close several factories with Factory Nine being the first to shut its doors.

Many workers of Factory Nine lined up outside in front of the building